Knowledge and Kindness: Powerful Antidotes

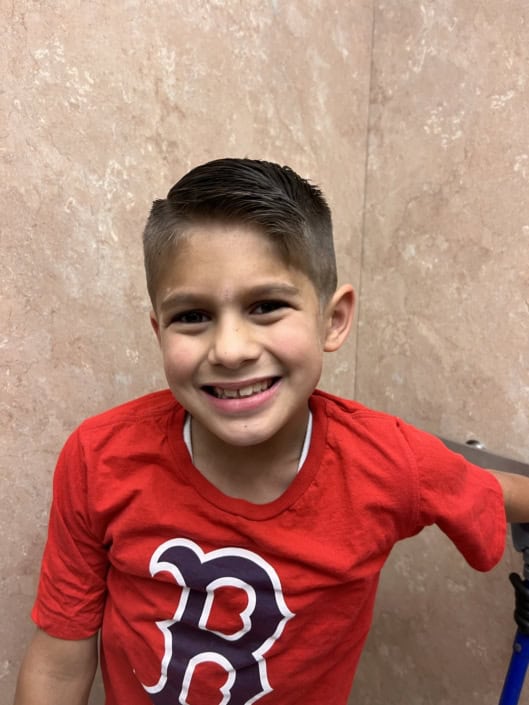

9-Year-Old Noah Holt of Massachusetts with Acute Flaccid Myelitis Shares Strategies for Staying Positive

By Colleen Lent, M.Ed., M.S.

In his written advisory Protecting Youth Mental Health, former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy writes that each child’s road leading to adulthood is different and difficult. Meanwhile, some children will face additional potholes and detours, potentially affecting their emotional health.

Nine-year-old Noah Holt of Amesbury, Massachusetts agrees with the U.S. Surgeon General’s assertion. At six-months old, Noah began showing signs of acute flaccid myelitis, a rare neurological condition that affects the spinal cord and weakens the muscles and reflexes in the body that some medical professionals refer to as “polio-like paralysis”.

Despite contending with this disability and the innate stressors of now being a fourth-grade student, Noah says embracing prosocial behaviors, including creating awareness about disabilities and cultivating kindness, have helped him navigate some challenging emotional paths. He shares some details about his strategies and philosophy that he believes can empower other children to traverse some mentally strenuous treks.

Noah recommends learning more about a particular challenge and sharing that newfound knowledge. When he was a first and second grade student at the Amesbury Elementary School in Amesbury, Massachusetts, he began noticing physical differences between himself and classmates. “I was upset about my disability one day,” Noah recalls. An idea formed. Noah asked his mother Elisa Holt if they could visit the Amesbury Public Library to find books on children with physical impairments. Elisa commended her son’s proactive approach. Reflecting back, Elisa says they realized finding books on AFM specifically would be difficult, however, due to the condition’s rarity. As of March 29, 2024, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has documented 746 confirmed cases since the agency began tracking AFM clusters amongst children in 2014. The mother and son research team didn’t find a multitude of books on children with physical disabilities. “Noah knew then we needed to do something,” Elisa says.

Noah and his mother then compiled a list of books about young individuals with physical disabilities and made a social media appeal for others to purchase the books for a book drive to benefit the Amesbury Public Library. After collecting about 187 books, Noah and Elisa realized they could share donations with other nearby Massachusetts libraries that included the Amesbury Elementary School in Amesbury, Flint Public Library in Middleton, and Charles C. Cashman Elementary School in Amesbury. In addition, he met with the Kassandra Gove, the mayor of Amesbury, Massachusetts to discuss his mission of making children’s books about disabilities more accessible. Gove, in turn, began stocking similar literature in her office for young visitors.

“People need to learn about disabilities,” Noah says. “People need to be inspired too.” He says accessing information about AFM helps him cope and understand his rare condition the National Institutes of Health describes as a “disabling illness.”

Noah also believes an open dialogue can also lead to advances in medical research and increase support for families contending with AFM, compelling him and his mother to share their family’s travails and triumphs. The Holt’s openness assisted with the development of the children’s picture book “No Time for the Moon” by Eric Arnold and Diane Roston, a collaboration of the CDC and Siegal Rare Neuroimmune Association. The narrative portion of the book features four friends in the AFM community embarking on an empowering journey of self-discovery that’s guided by a furry magical creature named Wouldya. The book also includes a frequently asked questions section and AFM guide for adults. Rebecca Whitney, SRNA’s associate director of programs and community support, says the Holts and other “incredible” members of the SRNA network provided first-hand experiences to help readers grasp the full impact of AFM on families.

“It’s extremely important for the CDC to continue to learn about AFM even though it’s rare,” Noah says. “Doctors and scientists need to learn the cause, effects, and treatment options.” Noah says he hopes his narrative can help the SRNA and CDC more fully understand AFM.

Sherry Cerino, founder of the Massachusetts nonprofit organization Ella’s Way of North Andover that educates children about inclusion and disabilities through literature written by its team of authors, says she understands Noah’s quest for information about acute flaccid myelitis. As a former registered nurse for 40 years, Cerino notes parents and guardians often grapple with how to talk with children about serious diagnoses. Similarly, the article Chronic Illness and Children by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry reveals that some adults believe they can shield their children contending with serious conditions from unnecessary angst by withholding information. The AACAP, however, recommends sharing age-appropriate information with youngsters, helping them understand their prognoses and accept recommendations and treatments to assist them physically and psychologically.

Cerino says after learning about Noah’s book drive and mulling over the AACAP’s recommendations, she and her team of authors developed Kindness Corner Kits containing books about disabilities and related materials that include stickers, activity sheets, and online story versions for classroom, libraries, and other public places.

Noah says he’s proud his initiative to make books more readily available to children has spread to other cities and towns in the Greater Merrimack Valley area of Massachusetts. For example, the Pentucket Lake Elementary School in Haverhill set up a Kindness Corner with donated literature from Ella’s Way in its school library. The 9-year-old says people with health challenges need to be heard. Noah contends being able to share and learn through books helps children when they’re feeling sad or mad about their condition. Noah believes conversations about different obstacles help cultivate compassionate conversations in a variety of settings.

Noah adds that children can spread kindness with simple gestures too. “Sometimes it’s everyday things,” he says. As a fourth-grade student at the Charles C. Cashman Elementary School, Noah says when a classmate falls or trips, someone could ask if the peer is okay. In turn, Noah says showing consideration provides a bonus. “It just feels good,” he says. Noah explains that kind deeds garner intrinsic rather than extrinsic rewards or motivation.

The “good” feeling Noah references acts as research fodder for medical and mental health professionals alike. In its article The Art of Kindness, the Mayo Clinic discusses the physiological and psychological outcomes of benevolent acts. Helping someone else can produce serotonin and dopamine, neurotransmitters that activate the reward and pleasure centers in the brain, while also releasing endorphins known as the body’s natural painkillers.

In his numerous podcasts and books, Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist with the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, discusses another benefit of acting kindly. Grant cites numerous studies indicating children consistently expressing consideration for other individuals perform better academically and future leadership skills for future endeavors. The New York Times bestseller author recommends parents ask their children at night to describe how they helped peers during the day instead of discussing individual achievements.

After a long day of attending school and a physical therapy session, Noah reflects on Grant’s discussion of the impact of kindness. “It gives everybody power,” he says. Noah’s belief echoes the words of the U.S. Surgeon General Murthy’s advisory that says it may appear counterintuitive for a person facing challenges to seek opportunities to help other people, but this prosocial behavior acts as potent antidote for the giver. Noah’s mother says her son’s positivity reinforces the family’s motto: “We are strong, and we try.” In a second personal story appearing on the CDC website, Noah elaborates on this mindset: “I know there can be challenges in life, but you can’t stay stuck in the challenges. If you say you can’t do it, you can’t do it. If you say you can do it, you can do it.”

Click the following links to learn more about Noah and read “No Time for Moon”:

Our “In Their Own Words” blog posts represent the views of the author of the blog post and do not necessarily represent the views of SRNA.